Job Tours at the National Art Center, Tokyo: Behind-the-Scenes Interviews by Interns! Vol. 5 Curatorial Department: Information Planning

Interview: Office of Information Planning Head and Senior Researcher Taizo Muroya

- <<Exhibitions, workshops, and other events Office Head Muroya has been in charge of>>

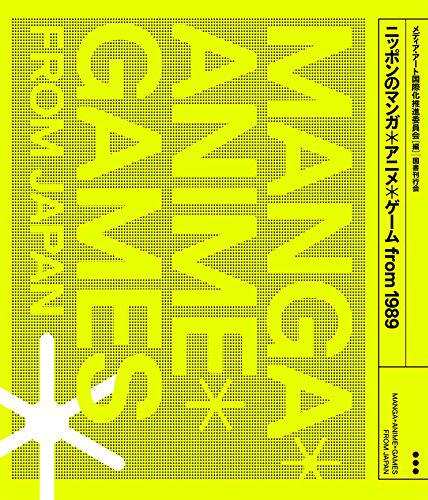

- “Manga*Anime*Games from Japan,” held in 2015

“NACT + JAA Animation Caravan 2020,” held in 2020, others

To start, tell us what kind of work you typically do!

The Office of Information Planning manages the museum’s website and collects a variety of information and materials. One of the defining features of the National Art Center, Tokyo (hereafter, “NACT”) is that it doesn’t have a standing collection, and seeking to instead gather information in its place has been the concept around which the museum was based from the start. For example, under the “art commons” project, which assembles information on exhibitions from across Japan, we have museums and galleries send us leaflets and postcards. We then put those into a database and make that information publicly available.

In addition, we provide technical support work works which use audio and visual equipment during exhibitions. For example, for a contemporary art video installation, we consider how to display it and provide support accordingly, something we’ve done since the museum first opened.

The Office of Information Planning also manages museum information security and everything else information-related.

I individually am also the assistant CISO* to the Independent Administrative Institution National Museum of Art, an organization of which NACT is a member. As someone in charge of all of the institution’s information security, my role is to consider policies and other matters.

*CISO(Chief Information Security Officer)

Please share what you majored in and studied in university!

I attended a STEM university. The school only had STEM departments, and in undergrad, I was in the informatics and engineering department. A combination of math, computers, and other stuff, the field of informatics and engineering is about analyzing and considering all sorts of things in the world. It also involves the application of physics, sociology, psychology, and more.

As an undergraduate student, I studied the principles of calculating computed tomography (CT). X-rays are images taken using X-ray radiation, but CT images aren’t so much taken as they are calculated. A computer is used to process the results of measurements taken by X-ray from a variety of angles and produce images. The computer makes use of calculation principles to do this with a variety of mathematical tricks, and it’s those tricks that I studied.

I continued to study this in my doctoral course, but it’s difficult to get a PhD with this kind of research and in the meantime I ended up working in an art museum. I had also concurrently studied color science. I learned about research into using colors to analyze the images in paintings, and I’m continuing to engage in research in that area today.

So along with your studies in informatics and engineering, you also researched color science and painting?

I didn’t study both fields together; rather, it was interesting how they were ultimately connected. In university, there were two instructors I wanted to study under. One was engaged in CT research, the other color science, and I couldn’t decide which direction to choose. As a result, I kept going back and forth between their two labs, but during my doctoral program, I started doing a part-time job at an art museum, and in part because that field also fit in with my life, I shifted toward color science.

There are a variety of approaches in color science, such as subjective or psychological approaches, but I decided to use mathematical methods. When we look at a painting, even if it was painted in a completely different era by someone who spoke a totally different language and lived an entirely different life, we still feel something. This made me think there was something there which went beyond subjective things like language and psychology. I realized that analyzing colors mathematically might be a better way to research that over looking at paintings and using words to talk about them. I just happened to be able to use the mathematical methods I had used when researching CT, and this tied the two fields together.

What led you from there to working at an art museum?

Back when I was studying the calculation principles of CT, the head of the information reference room at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (hereafter, “MOMAT”) sent a letter to the lab I attended. Around that time, art and other museums had just begun using email and creating their own online homepages, and the letter was asking whether there might be anyone in the lab who could help with that kind of stuff. I went to see him and find out what it was all about, and ended up starting off doing a part time job at MOMAT. The first things I did were making it possible for the museum to use email and setting up their website.

Please share how you got to NACT from MOMAT!

I joined NACT about two or three years after the office for designing the museum and preparing it to open was set up. Up until that time, I did IT work and helped with displaying video-based works at MOMAT. As I was doing work connecting IT devices for the museum and audio and video stuff for works of art on display, NACT’s design and prep office got set up and they contacted me for help.

I had originally envisioned myself getting a PhD to stay in university and work as a teacher, but helping out an art museum was also a worthwhile job and it had become particularly interesting once I started getting involved in the works put on display. It’s been difficult balancing this job with my research, but I’ve worked hard to make both a priority and that’s ultimately led to where I am now.

You’ve worked in art museums for a long time; is there anything which has been particularly memorable to date?

A lot of the work has been very difficult, but there are several jobs which I remember particularly well.

For the “Living in the Material World ― ‘Things’ in Art of the 20th Century and Beyond” held in 2007 to commemorate NACT’s opening, we did an absolutely massive exhibit in one of the gallery’s on the first floor. I helped with the exhibitions of the artists using video in their works. One of the artists, Michael Craig-Martin, had created this huge video work which combined the images from four projectors. He and his assistant came to Japan and I listened to what they wanted and prepared and set up the necessary equipment, but for some reason things just weren’t working right and I couldn’t figure out why.

The artist began to get worried, but then he turned to his assistant and said, “we should trust him (meaning me)” and I thought to myself, well, I better figure this out. In the end I fixed the problem and things worked out well, but I remember it being a really tough time.

Artists need my technical support, and so I want to realize what it is they want exactly the way they are expecting. Especially because one of the basic concepts behind NACT is not having a standing collection, I want to show people exhibitions that only NACT can do. Achieving to the fullest the wishes of artists who want to create installations in large-scale spaces is one way I think we can create exhibitions that fit NACT’s concept. Because those kinds of installations are not ones you can make part of a collection.

I also vividly remember taking part in the planning of an exhibition in 2015. The “Manga*Anime*Games from Japan” exhibition toured around Japan, Myanmar, and Thailand, coming and going over around a two-year period. Although it was very hard because we set up that exhibition from scratch.

Were you the one who chose the manga, anime, and games themes?

The director general at the time gave us the challenge of creating a comprehensive, broad level exhibition which would introduce Japanese pop culture to the world. We started with a team of six or seven researchers who created a book tracing the history of manga, anime, and games in Japan, then gathered works of art for each theme from among what was in there.

From right about 1987 to 1989 was when epoch-making works like Ghost in the Shell and AKIRA came out. 1989 was also the year Tezuka Osamu passed away and when the Heisei period began in Japan, and that’s the period we decided to focus on. After that, under the slogan of “1989,” we selected ten themes for works in the Heisei period for each of the genres of manga, anime, and games and divvied up the works for each them.

We aggregated all of this into a book, but it wasn’t possible to turn that book into the exhibition as-is. In all we had about 300 works and 30 themes, some of which overlapped or didn’t connect with the others, making it hard to just turn that into the exhibition. We really condensed that down and narrowed down the themes to create the final exhibition. We borrowed around 130 works from various places to put on display.

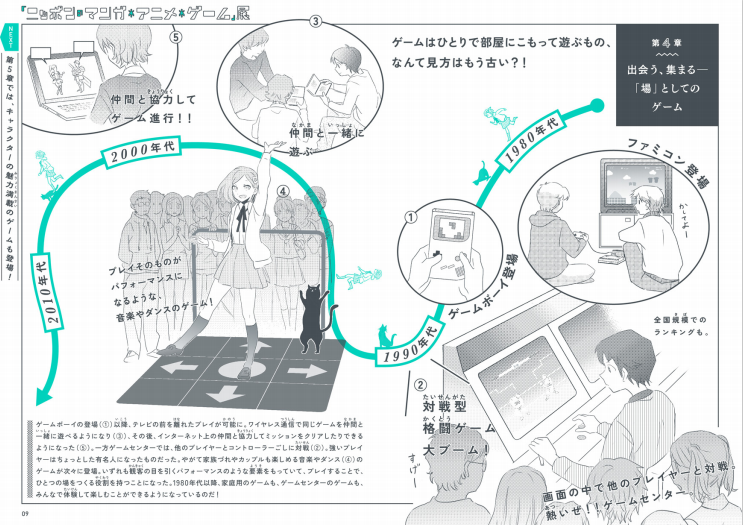

One of the themes in the exhibition was our reality as depicted through technology. The evolution of technology has had a significant influence on the worlds presented in manga, anime, and games. We also focused on how different content has resonated and led to works growing and expanding, such as the development of the Internet, Director Makoto Shinkai’s release of Voices of a Distant Star, and anime works created based on Vocaloid music.

In the field of games, today social games are at the height of their prosperity, but at that time, playing dancing games like Dance Dance Revolution had become a form of performance. We also looked at Final Fantasy and other games people all play together. Games have become a space of their own. In the Showa period in Japan, games had this negative image of something people did in dark, gloomy rooms, but the image of games today is nothing like that.

Compared to the Showa period, there are now many works which present fleeting glimpses of complex interrelations between the ordinary and the extraordinary. You might call it “post-Evangelion.” Both after the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake and the Great East Japan Earthquake, there were many works which depicted a link with real events, and a deeper connection between work and reality is one of the characteristics of manga.

The theme for the last part of the exhibit was the work of the creators, focusing a spotlight on all the effort creators put into their works. We presented several examples that great works were the result of uncompromising effort and not just something you could do because you had some computers.

I was also very stricken by the fact that this exhibition went on tour in Thailand and Myanmar. That year, Aung San Suu Kyi had won in the elections in Myanmar and the next year the country’s form of government was slated to undergo drastic change. I was worried about what would happen to the exhibit, but the exhibition period took place while the military was still in power and ultimately things worked out.

There was massive wealth disparity and children in extreme poverty, but still the country was much more well-off than we had imagined, and when we went to the market, there were huge numbers of books. There were temple schools like there used to be in Japan a long time ago, and because the temples taught children how to read and write, the literacy rate was extremely high. The cell phones the people used were also smartphones. They never had a flip phone period. Everyone was using Facebook and the like completely normally.

The reclining Buddha statues and Buddhist architecture was also amazing. The people of Myanmar are devout Buddhists, and everyone donates to the temples, so they are all kept very well-maintained. Nothing was old or worn out, and there was no “wabi-sabi” atmosphere like in Japan. All the Buddha statues were scrupulously clean. They’d have flickering LED halos and the latest technologies incorporated. Even though it was still Buddhism, the way they looked at it was completely different. Over there, the high heat and humidity would quickly rot away any wabi-sabi that was allowed, ruining things, which I guess is why they were so diligent in repairing and renovating everything. Those kinds of differences were very interesting.

Please share your favorite work from the exhibition!

It’s hard to narrow it down, so I’ll give two. The first would be Gran Turismo 6, a racing simulator game. When we went to explain the exhibition to the company which developed the game, they promised to make us special images for the exhibition and also showed me a supercar that had been super popular when I was a child.

The other would be Tsutomu Nihei’s Blame!. When I explained the exhibition concept to the deputy editor of the magazine publishing the manga, he told me I could take and use whatever scenes I wanted to. I stuffed a bundle of draft copies in my bag and chose what was around a 4-page spread to display. The work for that exhibition was sometimes extremely hard. I’d take the last train home or sometimes miss it and not go home that night, but I was also extremely happy that there were these kinds of things. But that kind of thing only happens with around one in every 10 exhibitions (laughs).

Please share what kind of work current interns do! In addition, is there anything you’d like future interns to study?

We have our current intern gathering information on various exhibitions. In particular, information on what kind of exhibition activities have been conducted in Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic. We’re investigating things like what has been cancelled, what has been postponed, what has been held online, and what additional measures have been taken when holding exhibitions offline. Ultimately, we want to visualize this information and compile it into a perspective on the exhibitions of 2020. Right now we have our intern putting piles of sticky notes on a huge sheet of paper so we can analyze overall trends and discuss them.

You asked what I wanted interns to study, but I think having them study something might be a little off. To be honest, I’m not quite sure what the answer would be or if there even is an answer. What you study might lead you somewhere or might end up being half-finished. That’s what happened with my own research, but it’s not like there’s a correct way to do things you can just aim for. If we could put out a problem we knew the answer to and have you solve it like an elementary school math drill, it might be easier for both of us but it wouldn’t be interesting.

Unlike the systematized study of schools, working in an art museum often doesn’t have clear answers. When you’re working with something where you don’t know what the end result will be, you work on it while considering and discussing what approaches you can take that will get you closed to the answer. I think that kind of attitude would be useful to an intern.

- [Interview and editing]

- Mayu Iguchi

Interned in the Office of Education and Promotion in 2020. Fourth-year Media Design student, Tokyo Zokei University (as of the time of this article).

Is also involved in planning workshops, etc. in her university. One of her favorite special exhibitions was “KASHIWA SATO,” held in 2021.